Tentatively, Photo London’s tenth edition moves away from traditional content and crowds

The worlds of art and photography are not the easiest of bedfellows. Despite their obvious similarities and shared concerns, the communities that inhabit these two spaces are often quite different. At the preview day of this year’s Photo London (until 18 May) these differences were laid strikingly bare—and the results proved surprisingly positive.

Celebrating its tenth anniversary, and under the stewardship of newly-appointed director Sophie Parker, this year’s fair promised a new approach. In a recent interview with The Art Newspaper, Parker confirmed an end to the fair’s tradition of naming a Master of Photography—often a straight white man—and said that, as far as she was aware, “this edition will have no pictures of Kate Moss”—a reference to the notorious “Kate Moss index”. She has also overseen the return of the Positions section, dedicated to unrepresented photographers, which this year features works by Palestinian-American image maker Adam Rouhana and British Indian documentary photographer, Kavi Pujara.

Yet, by the late afternoon in Photo London’s main pavilion, set in the courtyard of Somerset House, evidence of change was not immediately obvious. In traditional art fair style, champagne flowed and wearers of high heels clicked and clacked past impressive but predictable works by Sebastião Salgado and heavily manipulated landscape views. Booths were busy and interest appeared high, but those sought-after red “sold” stickers were sparse. Among the newer galleries, however, commercial success and changing tastes could be sensed.

Despite the long journey, Taiwan-based Chini Gallery were pleased with early sales

Photo: Graham Carlow

Taipei City-based Chini Gallery sold a 1.2 metre high portrait by Chou Ching Hui into the collection of a Norwegian museum before midday. The first-time exhibitors were delighted with the sale, which came in between £10,000 and £15,000. “[Attending the fair] is a very high cost and a long journey,” acknowledges Chiwen Tu, the gallery’s head of international development. “But the popularity of the work is beyond my expectations.”

In a fluctuating market dealing with tariffs and concerns around generative AI, buyers could be forgiven for returning to instantly recognisable photographers and subjects. Yet, in Somerset House’s West Wing, at the London-based Iconic Images—known for editioned, black and white prints of the stars of stage and screen by the likes of Gered Mankowitz and Norman Parkinson—sales were yet to materialise. The mood among gallery staff was buoyant, however, as it was at the nearby Peter Fetterman Gallery.

A long-standing purveyor of works by some of photography’s biggest names—Henri Cartier Bresson, Robert Capa, Don McCullin—Fetterman was still also awaiting his first sales, but didn’t appear worried. In the US, where his gallery is based, he describes an aggressive, “cash and carry” approach, whereas he finds UK buyers take more time to consider their purchases. “I’ve spent money before I’ve even sold,” the gallerist says with amusement, going someway to proving his own point.

In other areas of the venue’s sprawling corridors—considered, at least by some galleries, to be a more characterful location than the pop-up pavilion—money was changing hands. Paris’s Galerie XII sold three works by Susanne Wellm, who creates tactile works by combining photography with weaving, for between £6,500 and £7,000 each.

Hungry Eye gallery sold two works by Asha Swillens, whose work as a digital artist is influenced by her background in textiles

Photo: Graham Carlow

Meanwhile Amsterdam-based Hungry Eye Gallery, returning to Photo London for the first time in seven years, sold three images by the duo Schilte & Portielje in the fair’s first hour, each priced at £1,450. By early evening red stickers sat next to works by almost all of the gallery’s artists, with two works by Sara Punt priced at £1,800 each, two by Asha Swillens at £3,495 and £1,995 respectively, and an archival pigment print by Nina Hauben at £3,450. None of these image makers could be considered traditional in their approach—they embrace digital techniques, abstraction and collage.

This trend for the non-traditional carried out into Somerset House’s courtyard, where trainers and beer— not champagne and heels—were the order of the evening. The crowd appeared younger than in past years, more in keeping with the edgier, not-for-profit satellite event Peckham 24, than with the fairs of the art world. Could this younger crowd, their pockets not yet as deep and their tastes different to the older generation, be the driving force behind these lower price point, less conventional sales?

In the fair’s Discovery section, nestled in the bowels of Somerset House, it seems possible that this theory could pan out. Dedicated to emerging photographers and galleries, booths are smaller, the atmosphere more party-like and both the people and the work more varied than in the pavilion and wings above. The section’s curator, Charlotte Jansen—for whom this has always been the most exciting area of the fair—describes a “sharp shift away from portraiture towards semi-abstraction and abstraction across many booths”.

This could certainly be seen at London-based Victoria Law gallery. Here Venezuelan-born Lucia Pizzani’s photo-based works and sculptures, which explore colonialism and nature through materials including pre-Hispanic tree bark paper, were drawing attention. At the back of the crowded room, Doyle Wham, which markets itself as “the UK’s first and only contemporary African photography & light gallery”, was presenting heat transfers on linen by Justin Dingwall, alongside a triptych from Heather Agyepong’s popular 2022 series, ego death.

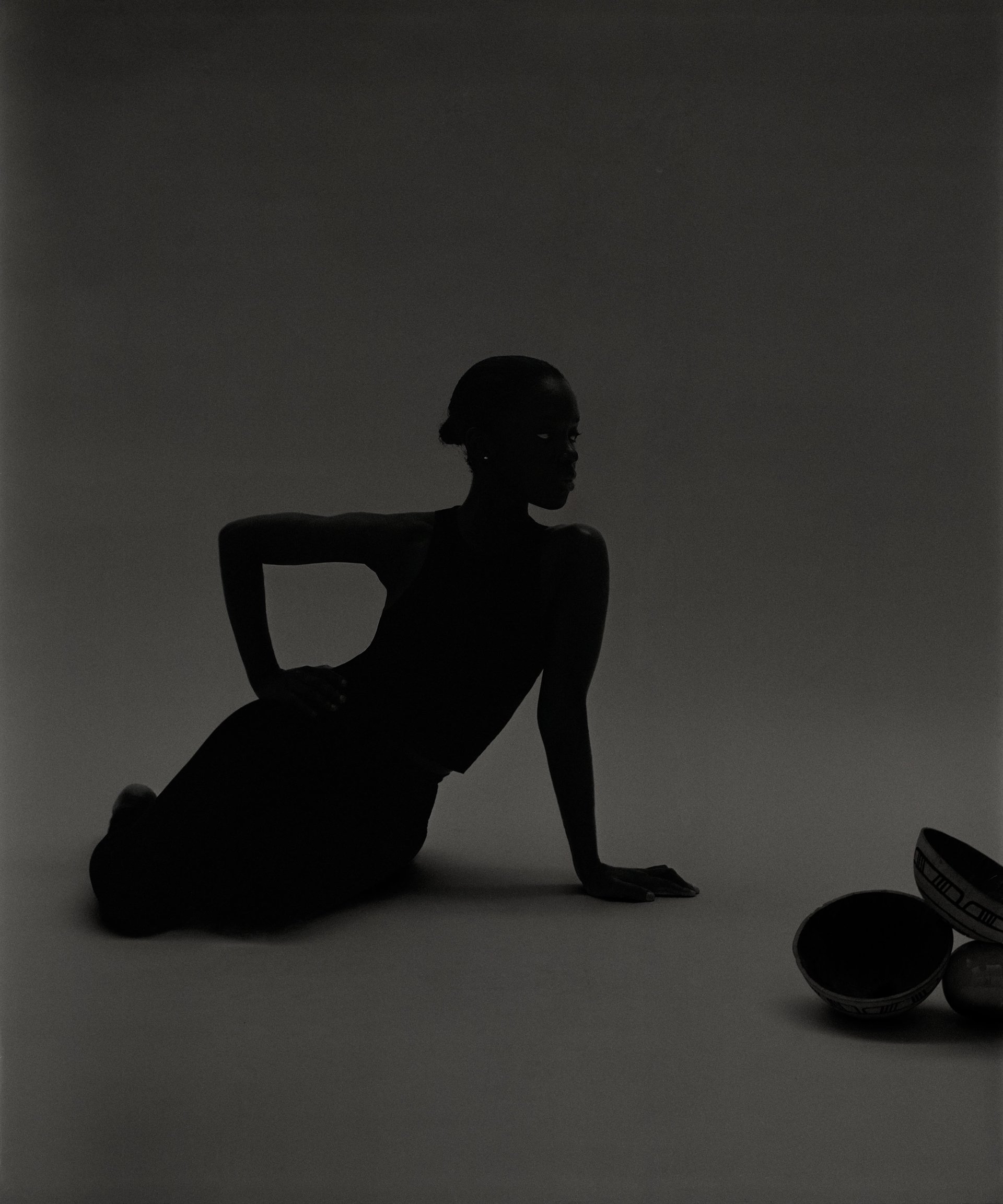

Doyle Wham, founded in 2020, returned to Photo London for what they describe as a “special” fourth year

Ori Inu 7 by Aisha Seriki. Courtesy of Doyle Wham

Sofia Carreira-Wham, the gallery’s co-founder, says this feels like the best year for the Discovery section to date—a success she attributes to the collaboration between Jansen and new fair director, Parker. “It really feels like an insight into what is kind of cutting edge and challenging in photography today,” she says. The young gallery made its first sale before the night was out too, parting with Nigerian multi-disciplinary artist Isha Seriki’s Orí Inú 7 for £1,250.

Back in Photo London’s main pavilion, as revellers began to thin out, a smattering of red stickers was revealed in their wake—but even here, where prices are considerably higher than at the booths below, buyers seemed to have made less traditional choices. The prominently positioned, Amsterdam-based Homecoming gallery sold two works by Aldo van den Broek, priced at £15,000 and £14,750 respectively. The large-scale pieces are made via processes involving acrylic, soil, wood and cardboard—wall captions offer no mention of a lens-based practice.

Of course, it is not all change. While this year’s fair will certainly score lower on the “Kate Moss index” than past editions, a few portraits of the supermodel were still to be found. Overall, however, Parker’s plan to “reward galleries that take risks” could be seen in action. And, if Photo London really is ditching artworld tropes in favour of the traditions of the photography world, it is a choice that appears to be paying off.