Ten top shows to see in New York during Frieze week

Jack Whitten: The Messenger

Museum of Modern Art, until 2 August

The first full-scale retrospective on the late great painter and sculptor Jack Whitten (1939-2018)brings together more than 175 works spanning his six-decade career. His large-scale mosaic-like compositions—made from hardened acrylic paint cut into thousands of tiles—figure prominently, as do his mixed-media assemblage sculptures. The show also spotlights early works, including a series made applying photocopier toner almost as if it were paint, and his visceral response to the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, at the height of the Civil Rights movement.

“Whitten defied traditional boundaries between abstraction and representation, race and nation, culture and technology, individual identity and global history,” says Michelle Kuo, MoMA’s chief curator at large, one of the exhibition’s co-organisers. “He made art matter in a world in turmoil.”

Installation view of Rashid Johnson’s Sanguine (2024) at the Guggenheim, part of the Chicago-born artist’s largest exhibition to date with almost 90 works in a wide array of different media Photo: David Heald; © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, until 18 January 2026

In Rashid Johnson’s largest exhibition to date, and his first at the Guggenheim, he has taken over the rotunda in style—hanging several plants from the skylight as a teaser to his artfully potted garden at the top of the museum’s ramp. The exhibition, named after a poem by Amiri Baraka, spans the breadth of Johnson’s career with almost 90 paintings, sculptures, videos, photographs and installations from the early 2000s to today.

As visitors move up the spiral, Johnson’s self-portraits as Black historical figures give way to sculptures with the artist’s characteristic materials such as shea butter, black soap, mirrors and LPs. Towards the end, dozens of glazed stoneware pots filled with real plants lead to Sanguine (2024), a giant installation of shelves upon shelves of potted flora, videos and other works. Nestled among them is a piano—musicians are invited to play surrounded by ferns and cacti throughout the show’s run.

Congolais (1931) by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet (1890-1960), the first African American graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design © Whitney Museum of American Art

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend an Inch

Brooklyn Museum, until 13 July

This Afro-Indigenous artist’s retrospective tells a long-overlooked story of grit in the face of adversity. Nancy Elizabeth Prophet (1890-1960) was the first African American graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, making a name for herself early in her career with her sombre and sensitive sculptural portraits, only a few of which have survived.

Despite her technical prowess, Prophet was marginalised in the art world, a position that forced her into poverty and near starvation at several periods during her life. Still, she never turned her back on her practice, expressing herself in carvings, reliefs and works on paper, a rare gathering of which are now on display at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Elements of Prophet’s personal archive are also on view, including examples of her correspondence with W.E.B. Du Bois—a lifelong friend and supporter of her work—as well as archival photographs and a diary from Prophet’s time in Paris.

The Hudson Valley-based artist Jennie C. Jones’s commission for the Met’s roof garden is a series of acoustic sculptures inspired by the museum’s extensive collection of musical instruments Photo: Hyla Skopitz; imaging: Met Museum © 2025

The Roof Garden Commission: Jennie C. Jones, Ensemble

Metropolitan Museum of Art, until 19 October

What sound could sculpture make? That is one of the many synaesthetic questions Jennie C. Jones conjures in her new commission for the Met’s roof garden. Her stark, powder-coated aluminium menhirs use stringed instruments as experiential analogues for Black contributions to the cultural canon, expanding the Hudson Valley-based artist’s longstanding interest in animating minimalist abstraction with sonic life. The Aeolian harp-inspired works are, by definition, played by the wind and don’t require musicians to be activated. Visitors must get in close to the sculpture to hear what it has to say. “The main entry point was that the Met has its musical instruments department, which I’ve gone to many, many times over the years,” Jones tells The Art Newspaper. “This cacophony of silence and the sonic imagination of wondering what all of these instruments would sound like emerged from that place.”

Rembrandt van Rijn’s A Jewish Heroine from the Hebrew Bible (1632–33), on view at the Jewish Museum in an exhibition exploring the biblical character of Queen Esther National Gallery of Canada

The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt

Jewish Museum, until 10 August

In 17th-century Holland, the biblical character of Esther played an outsize role in visual art. The brave queen who risked her life to save her people—celebrated every year on Purim, one of Judaism’s most festive holidays—became a symbol of the Netherlands’ fight for independence from Spain during the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648). The Jewish Museum brings this unique moment in time to life through more than 120 works, including paintings, prints, drawings and an impressive number of illuminated scrolls telling the story of Esther. As the exhibition’s title suggests, there are several Rembrandts represented here—notably, his painting A Jewish Heroine from the Hebrew Bible (1632-33), on loan from the National Gallery of Canada. Works by Rembrandt’s pupils and contemporaries—including Aert de Gelder, Jan Steen and Gerrit van Honthorst—depict scenes from the Book of Esther and, at the same time, provide an astute peek into life in the 1600s.

Trans Forming Liberty (2024) by Amy Sherald, who explores “what it means to be a Black American” Photo: Kevin Bulluck; courtesy the artist and Hauser and Wirth; © Amy Sherald

Amy Sherald: American Sublime

Whitney Museum of American Art, until 10 August

American Sublime positions Amy Sherald— the painter best known for her elegant portraits of the former first lady Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor, who was shot by the police in 2020—as a bard of the Black experience, centring African American subjectivity in the American canon. Her contemplative portrayals of everyday Black sitters offer a subtle spin on the American Realist tradition, foregrounding historically disenfranchised narratives and visual languages for a contemporary audience. Sherald’s perspective is partially informed by her time as an undergraduate student at Clark Atlanta University, a Historically Black College and University, which opened her mind to alternative modes of audience. In American Sublime, Sherald explores the ever-urgent “wonder of what it means to be a Black American” during a period of enormous flux and uncertainty throughout the country. Originally organised by Sarah Roberts at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the exhibition’s New York iteration was put on by the associate curator Rujeko Hockley and the curatorial assistant David Lisbon.

Still from Karimah Ashadu’s Machine Boys (2024), which won a Silver Lion award in Venice Courtesy the artist and Fondazione In Between Art Film

Machine Boys

Canal Projects, until 26 July

Karimah Ashadu’s Machine Boys (2024) had its world premiere at last year’s Venice Biennale, and the artist walked away with the prestigious Silver Lion for Promising Young Participant. The short film explores themes like hypermasculinity within Nigerian culture, focusing on the informal economy surrounding motorcycle taxis—commonly referred to as Okada, which are banned in Lagos—and the lives of their riders via first-person accounts.

Ashadu was born in London in 1985 and grew up in Nigeria, which she says “instilled a very deep sense of ‘Nigerian-ness’ and everything that comes with that”. Her practice explores issues of labour and concepts of independence within the social, economic and cultural contexts of Nigeria and its diaspora. She initially studied painting but had a desire for “something that was more immediate, that was more instantaneous”, she tells The Art Newspaper. “Film provided me with that.” She has recently returned to painting, but on found materials instead of canvas.

Another of Ashadu’s videos, Brown Goods (2020), is featured in MoMA PS1’s The Gatherers (until 6 October), a group show “grappling with global waste and excess”. Brown Goods explores themes of informal trade, value and race via the story of Emeka, a Nigerian man based in Hamburg, Germany, who left his homeland for Libya in search of economic opportunity. He recounts how, in 2011, the efforts of a “good Samaritan” led him to Italy, where he stayed in a refugee camp for nearly two years. He later made his way to Hamburg, where he had to start from scratch despite his academic qualifications and work experience. He now exports second-hand goods from Europe to African countries like Nigeria.

While the subjects Ashadu explores in her work tend to be heavy, her intention is not to lecture people but rather to draw them in with engaging work—leading them to pay more attention to important issues.

Reflecting on the legacy of the Amazonian rainforest: Adriana Varejão at the Hispanic Society Museum and Library Photo: Alfonso Lozano

Adriana Varejão: Don’t Forget, We Come From the Tropics

Hispanic Society Museum and Library, until 22 June

Taking centre stage in the Hispanic Society’s gilded uptown environs, Don’t Forget, We Come From the Tropics highlights the work of the Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão, whose practice explores the intersection of ecology, culture and art. The title is borrowed from a famous quip by the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins (1894-1973). Spanning painting, sculpture and a site-specific outdoor intervention, Varejão’s pieces reflect on the legacy of the Amazon Rainforest and the Yanomami people, who have been a focus of research for the artist for 20 years. Featured in the show are new iterations of Varejão’s Plate series, large fibreglass tondos sporting hand-sculpted three-dimensional elements derived from ceramics by the French potter Bernard Palissy (1510-89). Adorned with Amazonian flora and fauna, the plates are contextualised within the Hispanic Society’s storied holdings of Spanish Valenciana, Ming Dynasty Hongzhi porcelain and pre-Columbian Marajoara pottery.

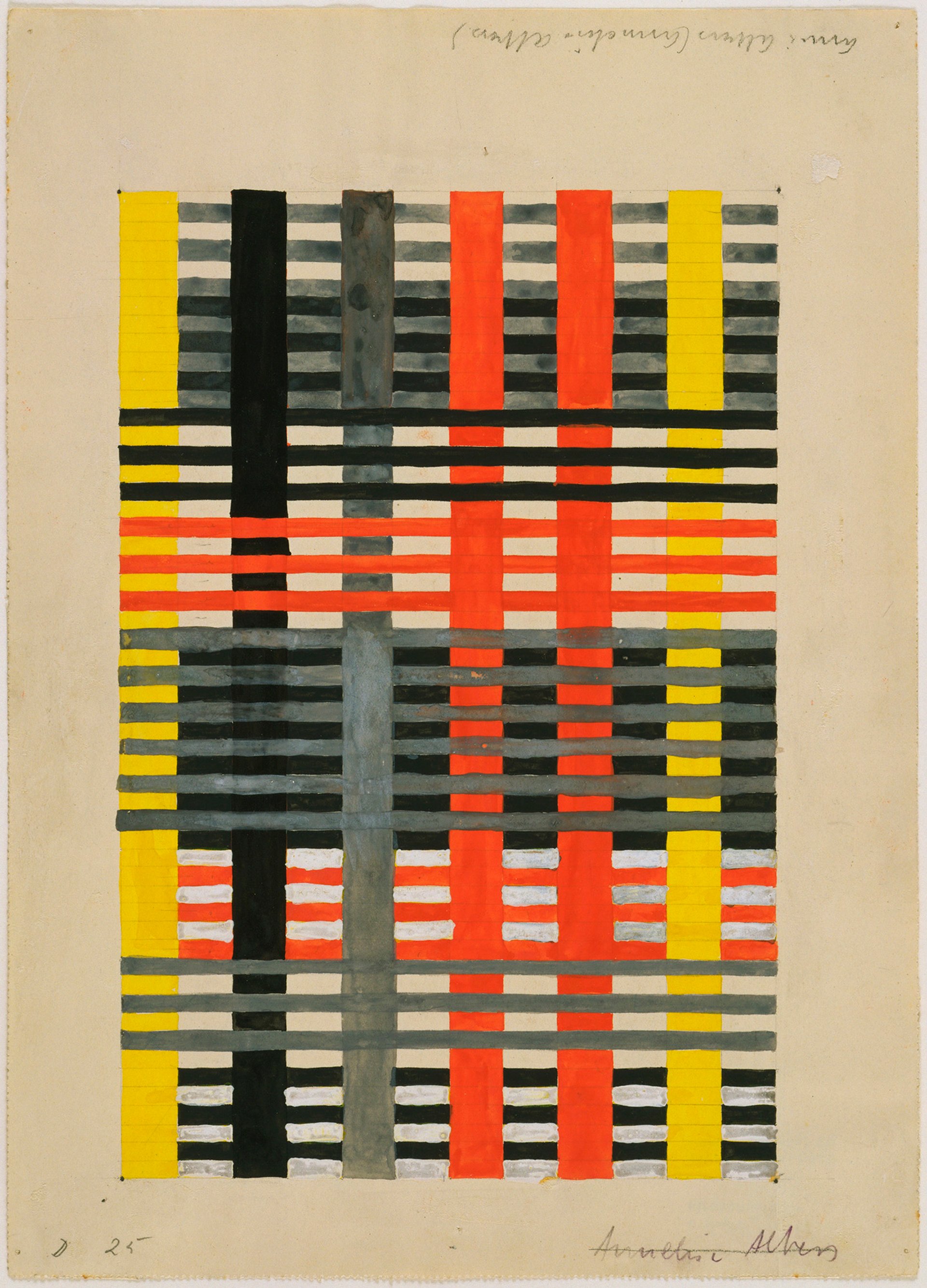

Anni Albers’s Design for Wall Hanging (1926), on show in Woven Histories at MoMA, which explores weaving through the lens of abstraction with around 150 works © 2024 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction

Museum of Modern Art, until 13 September

The MoMA curator Lynne Cooke has noticed a recent “surge” in weaving in contemporary art. “I was interested in why it was weaving rather than sewing or the domestic crafts,” she says. “The more I looked into it, the more I realised that it’s there from the beginning in the histories of abstraction. There’s the same abstraction in textile-making.” At its last stop, this expansive travelling show responds to MoMA’s historical engagement with the Bauhaus with around 150 works, by artists including Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl (who founded the Bauhaus’s weaving workshop). Woven Histories also features artists who may be less familiar—such as Ed Rossbach, who wrote books arguing for basketry as a fine art.

Mother and Child (1749-50), produced by the Chelsea porcelain factory and based on the print Le mérite de tout pais, after François Boucher © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie

Metropolitan Museum of Art, until 17 August

Looking back at the European craze for Chinese porcelain in the 1700s through the lenses of race, gender and class—and in the context of global capitalism’s infancy—Monstrous Beauty makes the case that porcelain artefacts could be seen as metaphoric vessels for Westerners’ essentialising fantasies about Asia (in general) and Asian women (in particular). It offers a feminist perspective on this dynamic by highlighting the role of European women as patrons of the international ceramics industry that sprang up to meet demand and, later, the women of Asian descent who critiqued and complicated the racist stereotypes propagated through historical porcelain.

This exhibition, curated by Iris Moon (the Met’s associate curator of European sculpture and decorative arts), brings together around 200 works spanning six centuries. It pairs objects like 18th-century dishes in the shape of sirens or featuring elaborate dragon designs with contemporary works by Asian and Asian American women artists. The exhibition, Moon says, “is both a story of enchantment and a necessary unravelling of harmful myths from the past—myths about the exotic—that have a hold over the present. It is time to retell the history of chinoiserie.”