‘We tried to train it like it was a kid in art school’: artist David Salle on using an AI model to enhance his painting practice – The Art Newspaper

David Salle is a notably articulate and thoughtful artist. His published interviews—covering the four decades since he captured critical attention in New York and Europe in the early 1980s with his first shows of paintings—and his own published writings (collected in How to See: Looking, Talking, and Thinking about Art, 2016) reveal an informed take on art history. They also elegantly express the development of his artistic process.

Salle is a regular contributor to the pages of The New York Review of Books. A January 2024 article for that publication, on the retrospective Alex Katz: Gathering at the Guggenheim New York (2022-23), demonstrates the controlled pacing in Salle’s prose, an immediate, precise turn of phrase and a clear-eyed, direct, often generous, critical outlook. “As you made your way up the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp,” he writes, “it was one god-damned masterpiece after another, triumphs of point of view, of touch and colour and composition. Of image. Of style.” And of Katz’s early New York subway drawings, from the 1940s, Salle writes: “They’re only quick sketches, but he was already absorbing a first principle: that specificity—of perception and also of the marks themselves—is everything; the generic is the enemy of art.”

Salle has brought this critical eye and concern for specificity to bear over the past two years when working with the engineer Grant Davis on training an artificial intelligence (AI) model to serve as a tool in his work. Salle and Davis have trained a custom version of Stable Diffusion, one of the leading image to text AI models, to generate intriguing machine-learning backgrounds recalling Salle’s existing paintings.

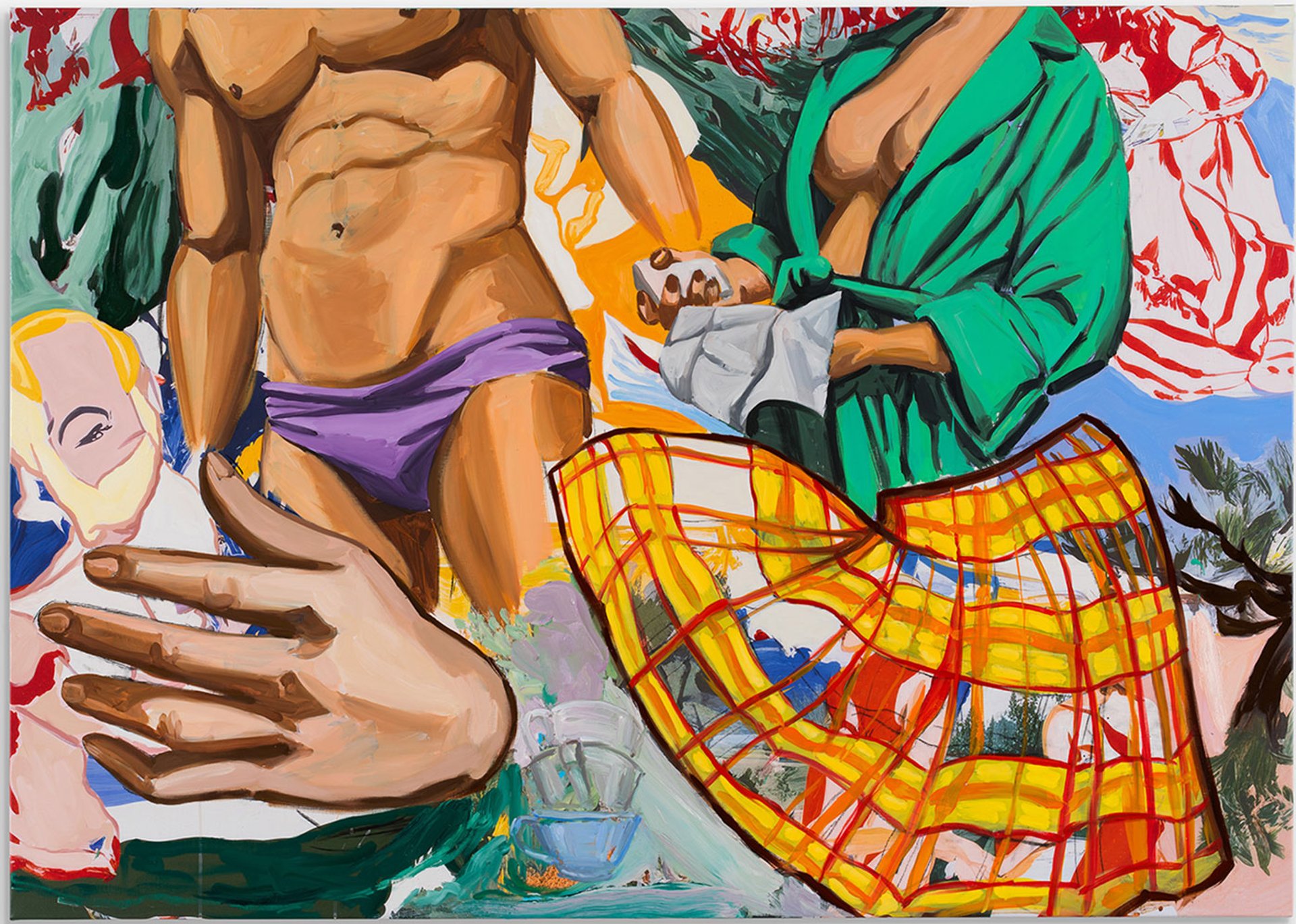

David Salle, Blue Coffee (2025), oil; acrylic; flashe; and charcoal on archival UV print on linen © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025. Photo: John Behrens. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

Salle has taken these images generated “with the machine”, printed them on linen as backdrops and then, working in response to them, has painted overlapping, dramatised groupings of vividly pigmented everyday objects: fragmented figures, male and female, in bathing suits or sun dresses; disembodied arms and forearms; plaid skirts and bikinis. The finished works are tinged with Salle’s trademark ambiguity and a lurking social anomie, expressed in a knowing post-Pop Art play. They carry mordant references to the commercial illustrator or cinema poster artist’s take on the American Dream, which was embedded within Salle’s 1950s childhood in the US Midwest. This new body of paintings is collected together in Some Version of Pastoral, at Thaddaeus Ropac in London, the latest works in a corpus first shown at the Gladstone Gallery in New York in November 2024.

A lengthy process of trial and error

To train their AI, Salle and Davis followed a process that he describes to The Art Newspaper as “lengthy trial and error” but one that has delivered intriguing, fruitful, results. The process, he says, has “been so rewarding … [and] inviting [of] my intervention” as an artist. In the process Salle’s own “ability to respond with a brush” has developed, he says, “in addition to the machine imagery evolving”.

That development, whether directly reciprocal or not, feels like Salle’s reward for putting in the hard yards training and learning to work with the AI. “You have to imagine this is something that doesn’t actually know anything,” he says. “So it’s a rather quixotic enterprise just to begin with. Why even bother to teach it something? It’s a machine. However, once trained, it’s useful.” Based on their the work they did with Stable Diffusion, Salle and Davis knew that the AI would be able to identify recognisable objects—a tree, a mountain—before they started feeding it art images.

David Salle, The Green Vest (2025), oil; acrylic; flashe; and charcoal on archival UV print on linen © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025. Photo: John Behrens. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

Salle’s first challenge in training his AI to produce interesting digital images was a problem with pixels. “The image is built out of pixels in a machine, and the pixels have no edge. The edge is simply one pixel up against another pixel,” he says. “Whereas in painting, not in all painting, but in the kind of painting that interests me, the edge is one of the main events… one of the signifiers of the painter’s painterly intelligence. That thing that we sometimes call style, a big component of that painter’s style resides in how she or he treats edges.”

The machine, he says, “simply has no idea what an edge is. So it’s a very funny conundrum in a way”. To address this challenge, Salle and Davis fed their AI with the work of Edward Hopper, Giorgio De Chirico and Arthur Dove. In each case Salle chose paintings from these artists’ work that illustrated specific painting ideas.

“The Edward Hopper was there in the mix to teach the thing about value pattern, about how light and shadow is used to create a sense of volume.” he says. “De Chirico was there for extreme perspectival space. Arthur Dove was there because his very lyrical liberal use of black as a way to weave.”

But the real training occurred, he says, “when I fed the machine dozens of paintings I made that were essentially thick-brush sketches of figures in space and domestic settings of household objects, of things in nature. But the subject was not important; what was important was the creation of an edge with a brush—that’s a meaningful mark and/or shape.”

David Salle, Washing (2025), oil; acrylic; flashe; and charcoal on archival UV print on linen © David Salle / ARS New York, 2025. Photo: John Behrens. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.

He found it surprising and remarkable how at this stage, in the final quarter of 2023, the feeding in of these thick-brush sketches, “the machine started to apply the translation effect that comes into play when a painter picks up a brush. So all of a sudden we had edges that were meaningful, we had edges that were translated into brushstrokes. And the brushstrokes describe forms.”

“That was really the core of it,” Salle says. “The De Chirico, the Hopper, we didn’t really need that. That was my first impulse because I thought, let’s train the thing how I was trained when I was a little kid in art school. You learn how to look at these artists for their certain formal qualities. But it wasn’t actually the thing that led to the interesting results. It was a number of fairly quickly executed brush paintings that allowed the machine to get a hold of the idea of what an edge is and how to use that.”

That was Salle’s starting point. The next stage was to train the AI on a group of paintings called the Pastorals (1999-2000) which, he says, “had already been broken up… into a faceted pattern of highly coloured kind of puzzle pieces that fit together in very specific colour harmonies and sometimes three or even four colour harmonies or palette.”

The question of Salle’s artistic response to the AI-generated background, where the combination of two points of view creates a third, conclusive sentiment, feels like a new stage in a long-standing aspect of his art.

“I start with an inability to see things singularly,” he said in an interview with ArtForum in 2003. “One thing automatically calls up another thing. And then that rhyme calls up a third thing to make a kind of chord. I have a musical analogy in mind.” That concept calls to mind his transition from installation work to his early 1980s paintings, characterised by paired spaces and striking juxtapositions, in which he tried to capture the fluidity of film montage, which he described in the 2003 interview as “two things in the right sequence make a third thing or, rather, allow the mind to make a new thing”.

When working with his AI to generate backdrop images, no text prompts are used. Davis has devised a lever to instruct the AI as to whether to create a work in a “similar” or “dissimilar” mode to its accumulated data. So the results, Salle says, “will either be very close to what you’ve fed the machine or it will be wildly divergent from what you fed the machine. and you just move that lever until you find the right balance point of similar and dissimilar”.

Throughout his career certain things have moved the Salle to action as an artist. For now one of the most fruitful has been his two-year engagement in building an AI that excites his imagination and challenges him to wield his brush in new ways.

- David Salle, Some Version of Pastoral, Thaddaeus Ropac, London, until 8 June 2025