How to see every painting by Leonardo da Vinci

The Adoration of the Magi (unfinished)When it comes to making a mark on culture, Leonardo is in a league of his own. He was, in modern terms, also a theorist of art, a mathematician, a student of optics, an architectural expert, a stage designer, an engineer (civil, military and hydraulic), an anatomist, a geologist and a physicist. No Renaissance figure left such a rich legacy of drawings and manuscripts.

His legacy as a painter was much less extensive, amounting to around 16 paintings that were predominantly or wholly by the master himself, with a further four or five works in which he intervened. It is also becoming clear that his workshop included skilled painters who could use the resources of the studio (cartoons etc) to produce what passed as “Leonardos”. Such a practice has resulted in modern disputes about attribution.

Along the way, he produced the world’s most famous painting, the Mona Lisa (1503-around 1516), as well as what may well be second most famous, the Last Supper (1495–98). For good measure, his Vitruvian Man (around 1490), a nude man inscribed in a square and circle, is the most familiar of all drawings.

In this quest to visit the key paintings, we journey to places where he worked, Florence, Milan and Rome, also France (which tends to lay claim to Leonardo on the basis of his service to Francis I at the very end of his life, and the presence of five paintings in the Louvre). An early Madonna and Child (1490) is in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. Another is in the Hermitage in St Petersburg.

The National Gallery in London is an essential port of call—there we can admire the uniquely surviving cartoon of the Virgin, Child, St Anne (?) and St John the Baptist (around 1507-16). One of the two versions of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder (around 1501-8) is on long-term loan to the National Gallery in Edinburgh. Special journeys are required to Washington, DC, which contains the last Leonardo to be bought by a public gallery, and to Krakow, which inherited the lovely and animated portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (around 1490).

Frustratingly, we do not definitely know the whereabouts of the world’s most expensive painting, the $450m Salvator Mundi, which has been the subject of polarised and acrimonious attribution and de-attribution—and therefore does not make this list.

Once we have completed this tour, we will have born witness to extraordinary originality of visual means and narrative content. Madonnas, in the hands of Leonardo, tell stories in a new kind of way, as do portraits. Overtly narrative paintings record the outer mechanics of inner emotions. The intensity with which Leonardo scrutinised nature finds expression in extraordinary visual effects as he persuades pigments and binders on white-plastered boards to do things they have never done before.

But looking back across the range of his pictures, each one seems to be its own unique experiment, as he tackles each of his subjects afresh. Not for Leonardo was Raphael’s systematic development of pictorial means. Given the ambitions that drove Leonardo’s desire that painting should surpass all the other arts and sciences, the surprise is not that he finished so few paintings but that he completed any at all.

Edinburgh

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder (around 1501-8), Buccleuch Collection, on loan to National Gallery of Scotland

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder (around 1501-8)

National Galleries of Scotland

This small Madonna is one of the best documented of Leonardo’s commissions. The work was ordered by Florimond Robertet, secretary to the French King who invaded Milan in 1499. It seems not to have been delivered until 1507. The Madonna and Child tells a story: Christ surges across his mother’s lap to grasp a yarnwinder, a cruciform device that symbolises the crucifixion.

The complication is that we have two equally fine versions, one in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch in Scotland and other that was formerly in the Lansdown Collection but is no longer traceable. Scientific examination of the two paintings has revealed similar and quite radical changes, as they evolved beside each other. Each picture has different passages of high quality. It seems that Leonardo used the commission to develop a saleable by-product.

Florence

The Annunciation (around 1475), Gallerie degli Uffizi

The Annunciation (around 1475)

Photo: Justin Benttinen

This oddly-shaped painting is rich in motifs taken from Leonardo’s studies with Andrea del Verrocchio, the sculptor and artist in many other media. The Virgin’s carved lectern is particularly reminiscent of Verrocchio. The picture is full of youthful striving: the laboured perspective, the emphatically folded draperies, the carpet of wriggling flowers in the “enclosed garden” (a signal of virginity from the Bible’s Song of Songs), the calculated curls of the angel’s hair, her birds’ wings, and, not least, the atmospheric delights of the distant maritime scene.

It may well have been undertaken in Verrocchio’s workshop and even commissioned from the master, with whom Leonardo was still working in 1476, his 24th year.

The Adoration of the Magi (unfinished)(around 1481), Gallerie degli Uffizi

The Adoration of the Kings (unfinished)(around 1481)

Photo: Justin Benttinen

The processional richness of Florentine Adorations has been overtaken by turbulent spirituality here, as the advent of the divine baby disturbs the world order. The crush of figures erupt in awe and confusion. In the background, an equestrian skirmish is triggered, while a half-ruined Roman structure seems to promise the end of the pagan era. There had never been an Adoration scene like this.

The work was commissioned for the Florentine monastery of San Donato a Scopeto outside the city walls. A document of 1481 records that Leonardo was in part to be paid by land. It is difficult to imagine how the unfinished picture might have been completed—there seem to be too many gesturing actors to fit on the pictorial stage. It is, nonetheless, magnificent and set in train a new kind of narrative intensity.

Krakow

Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, (‘Lady with the Ermine’,)(around 1490), Czartoryski Museum

Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, (‘Lady with the Ermine’)(around 1490)

Czartoryski Museum

The elegant lady shown cradling a white ermine in this portrait is today identified as Cecilia Gallerani, Duke Ludovico Sforza’s mistress. The duke is by implication present as the subject of Cecilia’s sideways glance. Cecilia was a woman of sophisticated tastes and a friend of the leading patron Isabella d’Este of Mantua, who asked to borrow the painting in 1498 to judge its merits.

The large but svelte ermine, painted with great refinement, is as artfully poised as the sitter. It has been included because of its allegorical significance: according to animal lore, the fastidious creature with its pure coat would rather be captured by a hunter than tarnished by soil when escaping across muddy terrain. As such it signified purity.

London

The Virgin of the Rocks (around 1496-1508), National Gallery

The convoluted history of the 1483 commission of this scene (see listing in Paris section) is difficult to follow, but when the painter left Milan in 1499, the version destined for the altarpiece in the church of San Francesco Grande was unfinished. When Leonardo returned in 1507, he eventually produced a picture, perhaps finished in part by assistants. Some brilliant passages of paint handling, as in the angel’s face and hair, are accompanied by more routine replication of such features as the rocks.

The Virgin of the Rocks (around 1496-1508)

National Gallery, London

There are some minor changes, most notably in the elimination of the angel’s pointing gesture, though scientific examination indicates that Leonardo originally sketched in a quite different composition with larger figures and with the angel holding the infant Christ. In the final analysis he sensibly resorted to painting something closer to a replica of the Louvre version.

Milan

The Singer (or ‘The Musician’, unfinished)(around 1485), Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

The Singer (or ‘The Musician’, unfinished)(around 1485)

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

While in Milan, Leonardo was much involved with music, which he regarded as the second highest art after painting. He designed theatrical settings and costumes for great musical events in the city and other northern Italian courts. He was himself admired as a player of the viola da braccio (an ancestor of the violin).

The subject of the portrait was probably the performer and instrument-maker Atalante Migliorotti, who accompanied Leonardo from Florence. In any event the sitter is a singer, as is evident from the rather damaged sheet of music. The man’s thoughtful head is strongly modelled, with a typical Leonardo cascade of curling hair. On the other hand, the singer’s fur stole remains as only an underpainting.

The Last Supper (1496-around 1498) refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie

The Last Supper (1496-around 1498)

Photo: demerzel21

Leonardo devoted very sustained attention to this mural of the momentous story of Christ’s final supper, which according to biblical accounts took place in what is known as the “upper room. The coffers of the ceiling and diminished tapestries create a systematic perspective and set up a plunging space, which is cunningly isolated from the space of the refectory by the upper cornice, behind which the coffers ascend.

Within the perspectival box, the crowded disciples individually react with vivid expressions and gestures to the tranquil Christ’s pronouncements on the Eucharist (the bread and wine standing for his body and blood) and his immanent betrayal by Judas. The painting of the Last Supper coincided with Leonardo’s research into the way that the brain and nerves drive the external expression of inner impulses.

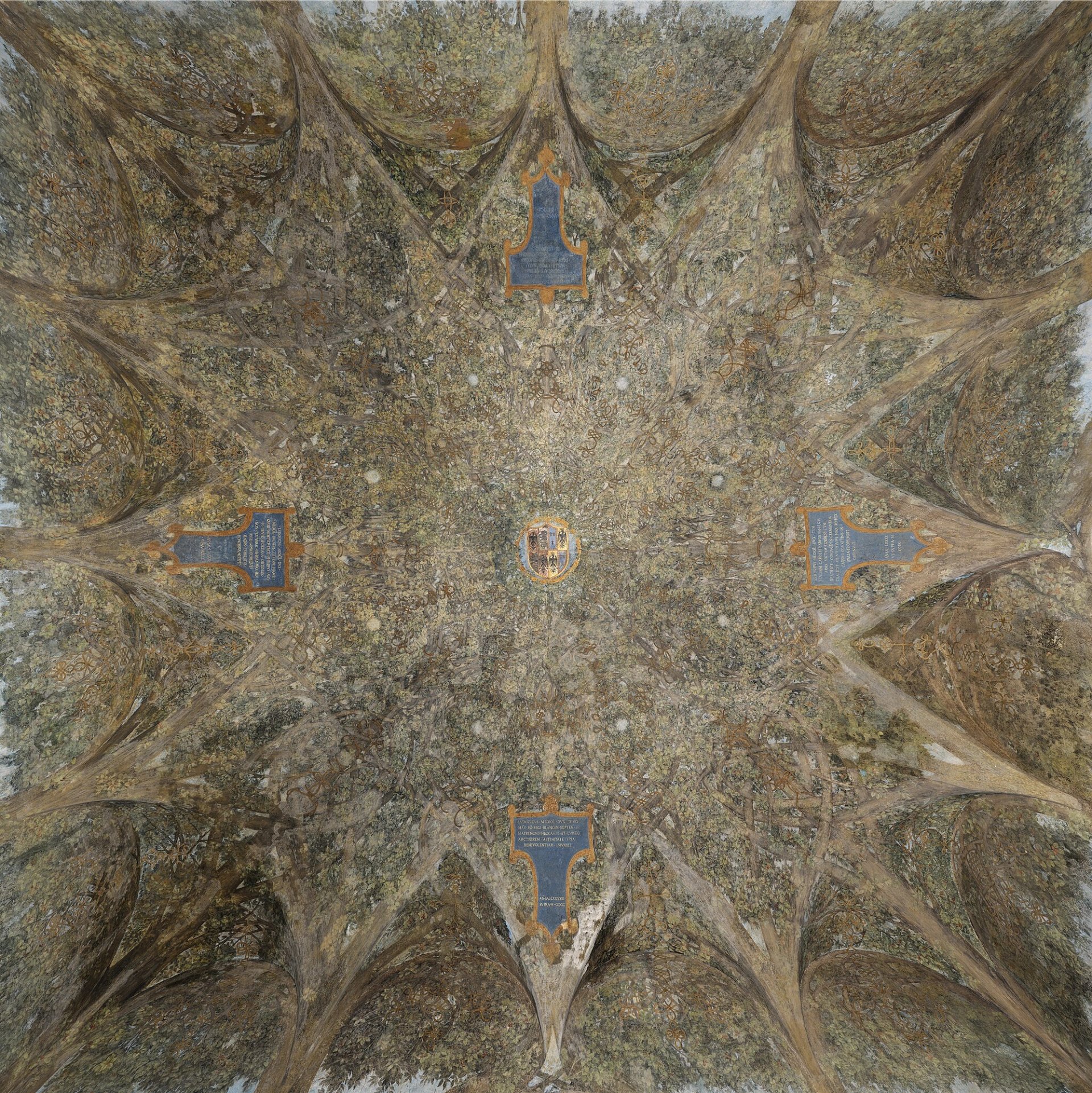

The Sala dell’ Asse (around 1498-99), Castello Sforzesco

A view of the The Sala dell’ Asse (around 1498-99)

Photo: Hoclab

The wall and vault painting in the spacious “room of the boards” in the Sforza castle was Leonardo’s largest surviving courtly decoration. A set of 16 mulberry trees (symbolic of Ludovico) rise at floor level from strata and rocks, branching out in mathematical knots in the vaults and ceiling. An interwoven gold thread signifies Beatrice, the duke’s wife, whose union is also celebrated in the heraldic shield at the centre of the ceiling.

Recent restoration of the damaged murals has given some insight into the botanical accuracy of the arboreal fantasy. Close examination shows that Leonardo required assistants to complete the repetitive motifs according to a tight timetable.

Munich

Madonna and Child (around 1477), Munich Alte Pinakothek

Madonna and Child(ca. 1477), Munich Alte Pinakothek

Munich Alte Pinakothek

As in The Annunciation (see listing in the Florence section), there is a sense of a young and gifted painter stretching his pictorial muscles in this most conventional of subjects. The Virgin’s face and knotted braids of hair are straight from the Verrocchio repertoire. We catch our first glimpse of Leonardo’s blue mountains. Nature has also been brought indoors, in the form of the blood-red carnations that the Child attempts to explore, and a posy of shining flowers in a glistening glass vase. Leonardo has particularly enjoyed the scintillating light on and in the crystal clasp of the Virgin’s dress. The child is not posed elegantly or for sweet appeal. The red flowers may represent Christ’s sacrifice to come.

Paris

The Virgin of the Rocks (begun in 1483), Musée du Louvre

The Virgin of the Rocks (begun in 1483)

Musée du Louvre

The Virgin of the Rocks is the first painting after Leonardo’s emigration to Milan under the Sforza. The commission was granted jointly to the artist and two Milanese brothers in 1483. It involved painted panels and polychroming for a huge carved altarpiece meant for the church of San Francesco Grande, Milan. Leonardo’s central panel of the holy figures immersed in a mysterious grotto was unprecedented.

Leonardo’s depiction of the Madonna and Christ encountering the infant St John the Baptist and an angel on their journey to Egypt seems not to conform to the strict stipulations of the contract. There was a legal dispute with the commissioners, centred upon Leonardo’s failure to deliver the work. The confraternity had a long wait for their picture: the replacement was not received until 1508.

It seems likely that the Duke of Milan commandeered this original masterpiece in 1494 as a wedding present for Bianca Maria Sforza of Milan and the Emperor Maximillian II.

Portrait of a Lady (‘La Belle Ferronnière’, or Lucrezia Crivelli) (around 1486), Musée du Louvre

Portrait of a Lady (‘La Belle Ferronnière’, or Lucrezia Crivelli) (around 1486)

Musée du Louvre

At first sight, this portrait of a lady seems less impressive than the Cecilia Gallerani (see the Krakow section of this list), but it has its own quiet merits. The sitter similarly looks sideways to our right, again by implication at Duke Ludovico Sforza, her lover. The use of a parapet behind which the sitter is seated, setting up the sitter rather like a sculpted bust, was fashionable motif in the northern Italian courts and Venice. The form of the sitter’s head is painted with a virtuoso’s conviction. As always, the jewellery is realised with extraordinary optical precision.

Views on the sitter’s identity have fluctuated unnecessarily. Court poems record Leonardo having painted an accomplished portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli, a later mistress of Ludovico. It seems that Leonardo was favoured for intimate portraits, while more formal ruler portraits of the duke and his family were assigned to regular court artists.

Mona Lisa (Portrait of Lisa del Giocondo)(1503-around 1516), Musée du Louvre

Mona Lisa (Portrait of Lisa del Giocondo)(1503-around 1516)

Musée du Louvre

This most famous of paintings began in 1503 as a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, an impoverished Florentine aristocrat and the wife of the trader Francesco del Giocondo. More important projects intervened and the work was not completed in Florence. The unfinished portrait travelled with Leonardo to Rome in 1513, where his patron, Giuliano de’ Medici expressed interest in it. The panel accompanied Leonardo to France in 1513, where, via circuitous routes, it entered the collection of Francis I.

During this time the portrait evolved to become a “universal picture” into which Leonardo poured his optical knowledge of light and shade, atmospheric perspective, the physics of drapery, the “body of the earth”, the body of a woman, and the “look” of moist eyes, soft skin, pink lips and cascading hair. The woman assumed the role of the “beloved lady” of Florentine poetry—beguiling but inaccessible.

The Virgin, Child and St Anne with a Lamb (around 1507-16), Musée du Louvre

The Virgin, Child and St. Anne with a Lamb (around 1507-16)

Musée du Louvre

Projects for the difficult composition of the Virgin, Child, St. Anne (or Elizabeth) and either St John the Baptist or a sacrificial lamb seem to have occupied Leonardo from around 1500 onwards. On his return to Florence from Milan, he proved his powers by exhibiting a cartoon of the Virgin, Child, St Anne and a Lamb. There is no surviving painting. There is a second later cartoon that does survive (London, National Gallery), in which the infant St John features, which suggests that the older of the women is Elizabeth, St John’s mother.

This leaves the painting in the Louvre. The three tender figures and captive lamb are rhythmically integrated in a way that disguises their physical improbability. The hazy mountain-scape manifests Leonardo’s intense studies of ancient geologies. It was worth waiting for.

St John the Baptist (around 1508-16), Musée du Louvre

St John the Baptist (around 1508-16)

Musée du Louvre

If St John is not the last of Leonardo’s paintings, it should be. It is a meditation on the ultimate unknowability of the spiritual world from the perspective of our earth-bound senses, very much in tune with Dante.

The saint points in a literal manner to the heavenly source of spiritual power, while his mysterious smile teases us that we cannot know what he knows. If this seems too mystical for our standard characterisation of Leonardo, we should note his unqualified praise of the “Holy Books”.

Paradoxically, the visual technique he uses is scientific. Islamic optical science, above all Ibn al-Haytham’s On Appearances, as transmitted though medieval philosophy. This did not so much confirm the geometrical certainty of optics as it emphasised the complex ambiguities of seeing. St. John is slippery—visually and spiritually.

Rome

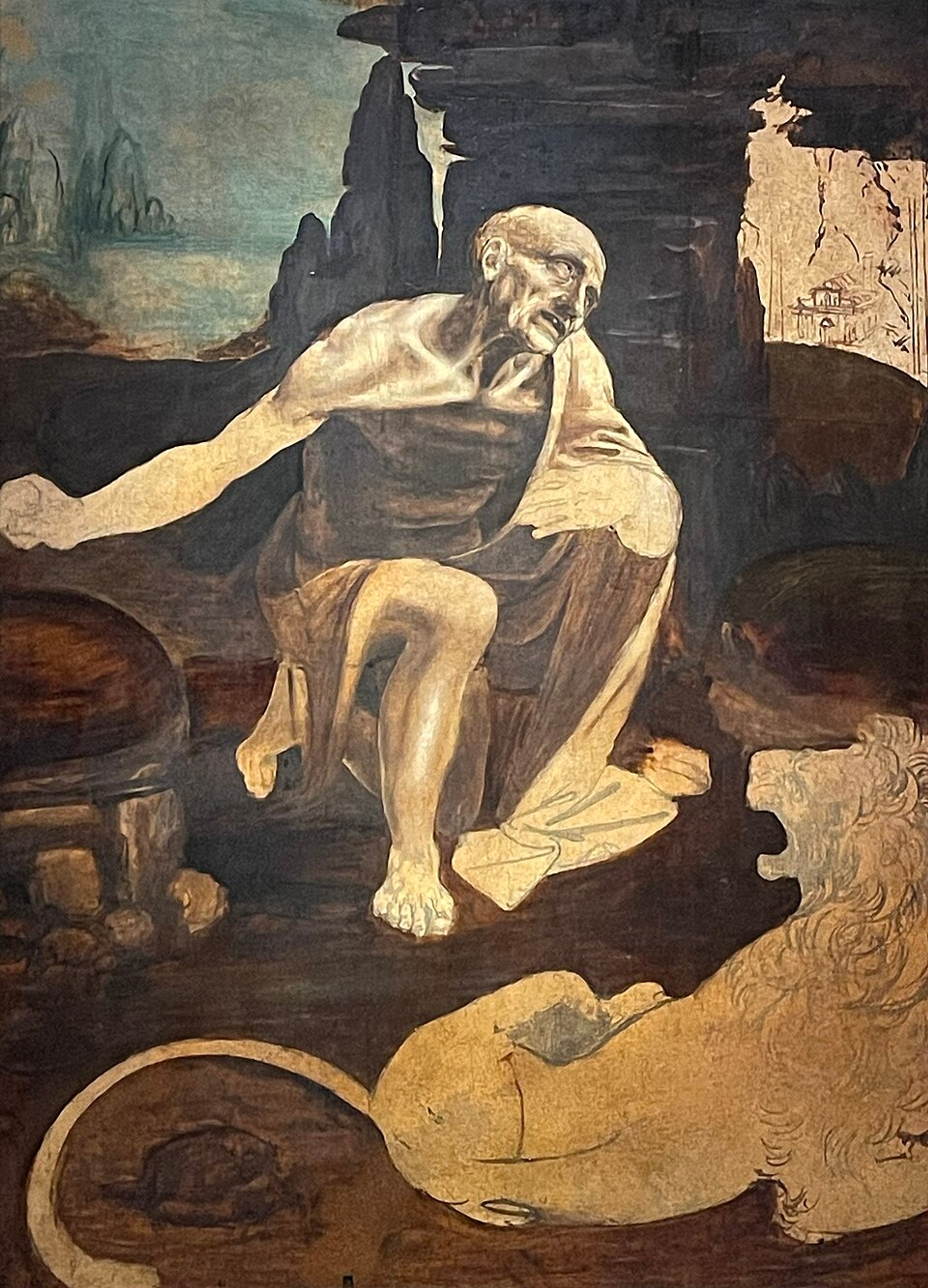

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (unfinished) (around 1481 and maybe later), Vatican Museums

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (unfinished) (around 1481 and maybe later), Gallerie degli Uffizi

Photo: Hay Kranen

Another unfinished painting, and it has also been mutilated. The portion of the walnut panel containing the saint’s agonised face had once been cut out as a separate picture. The remainder of the panel was cut into four pieces. Improbably, cardinal Joseph Fesch, a major collector and potent cardinal in the Napoleonic era, claimed to have found the separate fragments and reunited them.

The damage to this work—which is little more than a tonal underdrawing—seems to underscore the ravaged state of the saint in a harsh landscape as he prepares to beat his penitential breast with a stone, a self-inflicted punishment for his pagan tendencies. He is joined by a silhouetted lion, from whose foot—according to the legend—he had previously removed a thorn.

St Petersburg

The Madonna and Child (the ‘Benois Madonna’) (around 1480), State Hermitage Museum

The Madonna and Child (the ‘Benois Madonna’) (around 1480)

State Hermitage Museum

Here Leonardo engages in a new drawing style which allows the interweaving of form and motion. The draperies are now more concertedly rhythmic and responsive to the underlying bodies. The strongly directional light also serves to integrate the forms. The figures’ expressions—one smiling and the other carefully observing—converge on the complex knot of touching hands that centre on a bunch of small white flowers. The blossoms, significantly are cross-shaped. She smiles innocently. He intuits the future.

The blank window in the darkish room is unexpected. There is no sign that it once enclosed a landscape, and it may instead be a way to concentrate attention on the right upper quarter of the composition.

Washington, DC

Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci (around 1476-78), National Gallery of Art

Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci (around 1476 – 1478)

National Gallery of Art

Ginevra, part of a prominent Florentine family, was a favoured member of the Medici court. Her direct, indifferent stare was quite exceptional for a portrait of a woman at this time. Leonardo again favours dazzling details in the medium of oil paint, not least in the electric curls and sheen of his subject’s hair, set off against the spiky branches of juniper (ginepro) that pun on her name. The sharpness of the foreground is set off by the elusive, watery landscape in the distance.

We know from a decorative wreath on the reverse of the panel that patron was the Venetian ambassador, Pietro Bembo, who is mentioned in formulaic Medicean poetry as her lover.

The wreath also tells us that the lower third of the panel has been cut down, Ginevra’s hands probably taken with it.

- Martin Kemp is an art historian and emeritus professor of art history at the University of Oxford