How the rise of commercial engraving in the late Renaissance helped spread global interest in the papal conclave

With the conclave of cardinals meeting on 7 May to elect a new pope, who will become the 267th leader in succession of the Catholic Church, there is a global concern with the historic minutiae of the conclave’s closed, secret voting sessions. That concern is dramatically captured in the fictional hit movie Conclave (2024), downloads of which have surged since the death of Pope Francis on 21 April.

Public interest in the process of papal conclaves has deep roots in the 2,000-year history of Christianity and in the ever-consequential election of its spiritual leader, who provides liturgical and moral guidance to 1.3 billion Catholics as well as being proprietor in trust of the great library, art collection and historic church buildings belonging to the Vatican. Engravings and etchings depicting the papal conclaves of the day, dating from the mid-16th to mid-18th centuries, reveal an art historical aspect to the mass interest in papal succession.

These prints were aimed at the Roman tourist market, made up of the pilgrim faithful and increasingly of the would-be milord connoisseurs, who travelled to the Eternal City in growing numbers taking advantage of improved coaching technology and safer sea travel. Being present at a papal enclave, an event with real-world consequences, added to the frisson of visiting the remains of ancient Rome as they were adorned by the great humanist art patron popes— Julius II, Paul III, Paul V and Urban VIII among them—in both collecting classical statuary and commissioning art and architecture from Raphael, Michelangelo, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, their followers and rivals.

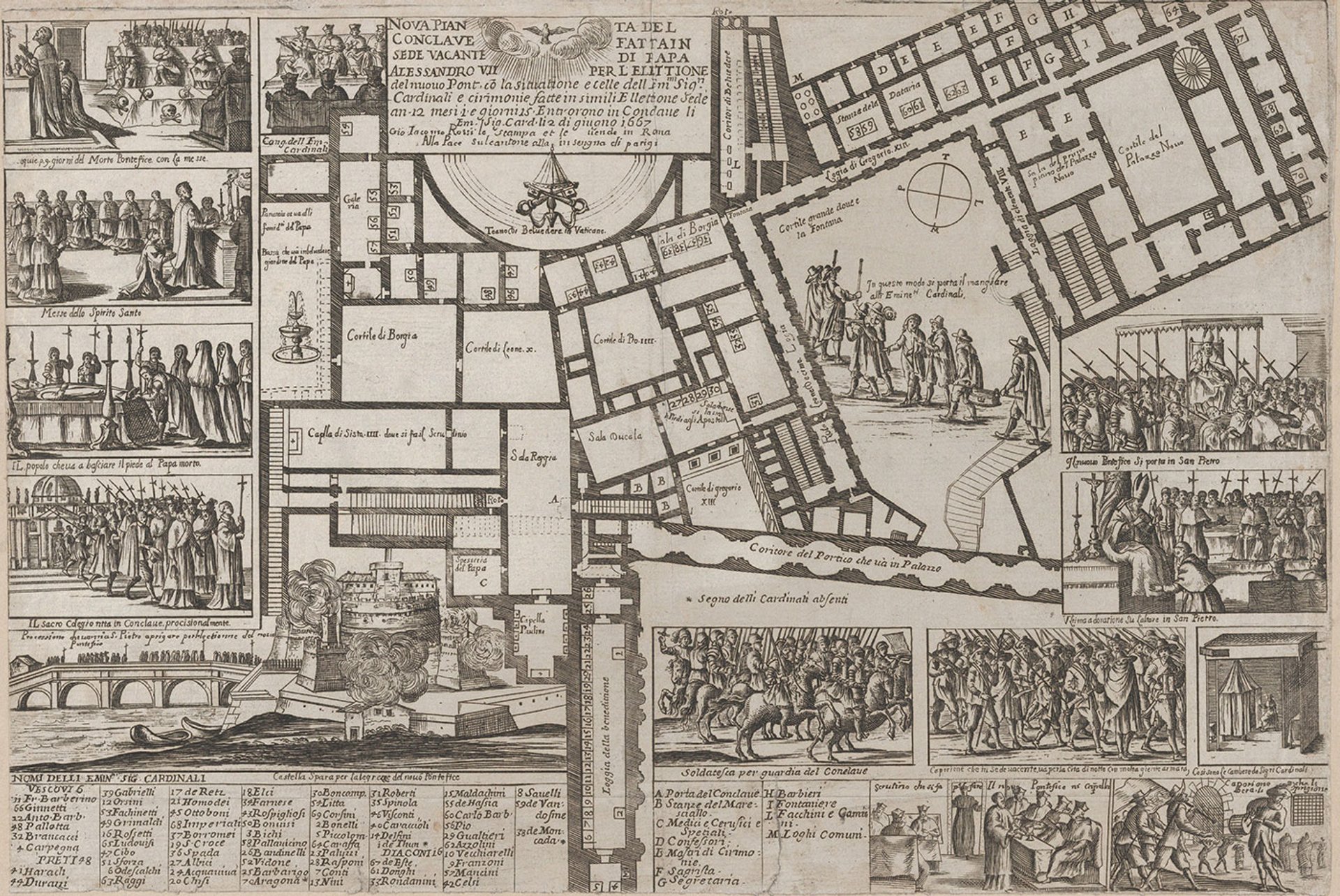

Detail from a 1667 papal conclave etching published by De Rossi, in Rome, of cardinals offering mass to the Holy Spirit and people queueing to pay their respects to a recently dead pope lying in state The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Google Arts

The conclave prints cover the ceremonial that surrounds the sede vacante—the time following a Pope’s death when the throne of St Peter is temporarily vacant—which has remained largely unchanged in 750 years. Following the public announcement of the pope’s death, there is the lying in state, the offering of masses to the Holy Spirit, nine days of official mourning that precede the meeting of the cardinals in conclave to elect a successor, the election proper, and finally the announcement of the new pope to the world.

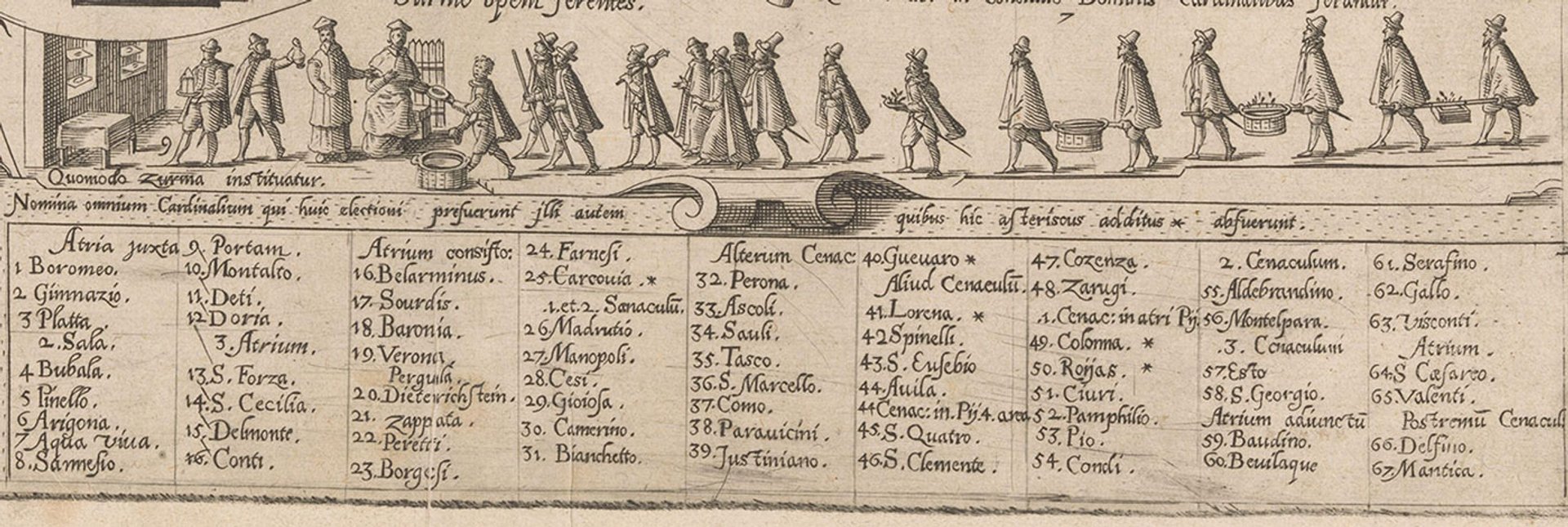

The images and captions in these Renaissance and early-modern engravings cover security arrangements, with Swiss Guards and mounted cavalry protecting the walls around the Vatican palace, and conclave officials overseeing the keeping of secrecy. A key element of this was checking for illicit messages going in with the cardinals’ daily food supply, and for messages coming out, including marks on the bottom of used dinner plates that might convey recent voting patterns either to the city’s bookmakers or to the well-funded ambassadors who represented the Catholic monarchies of Spain, France or the Holy Roman Emperor.

The visual narratives also cover the varied means of announcing the news of a new pope, which might in the 16th and 17th centuries have been signalled by cannon fire from Castel Sant’Angelo to the east of the Vatican, or with a signal given to the waiting crowds from a high chapel window.

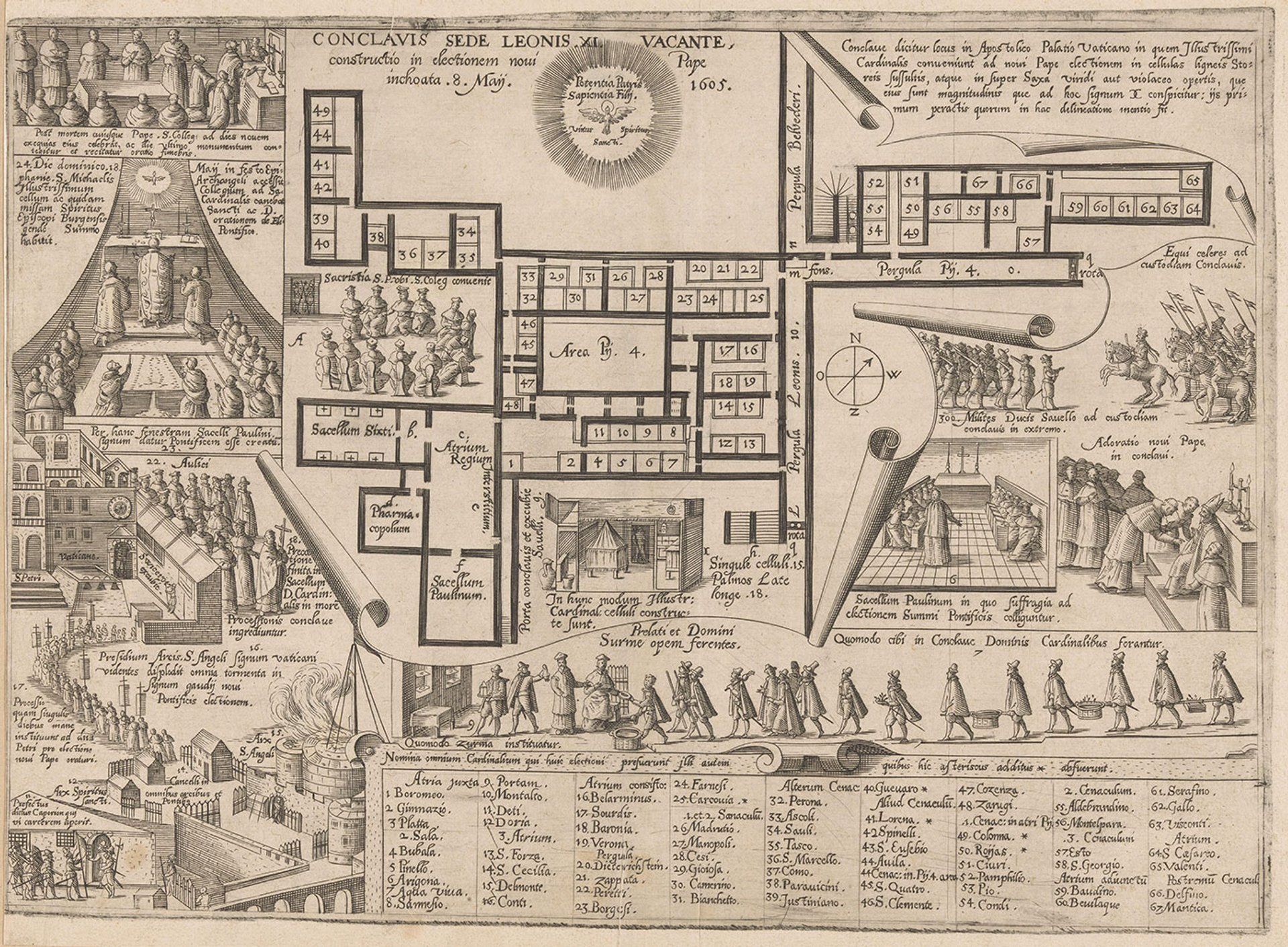

A conclave plan engraving published in 1605, the year in which Camillo Borghese was elected Pope Paul V piemags/rmn / Alamy Stock Photo

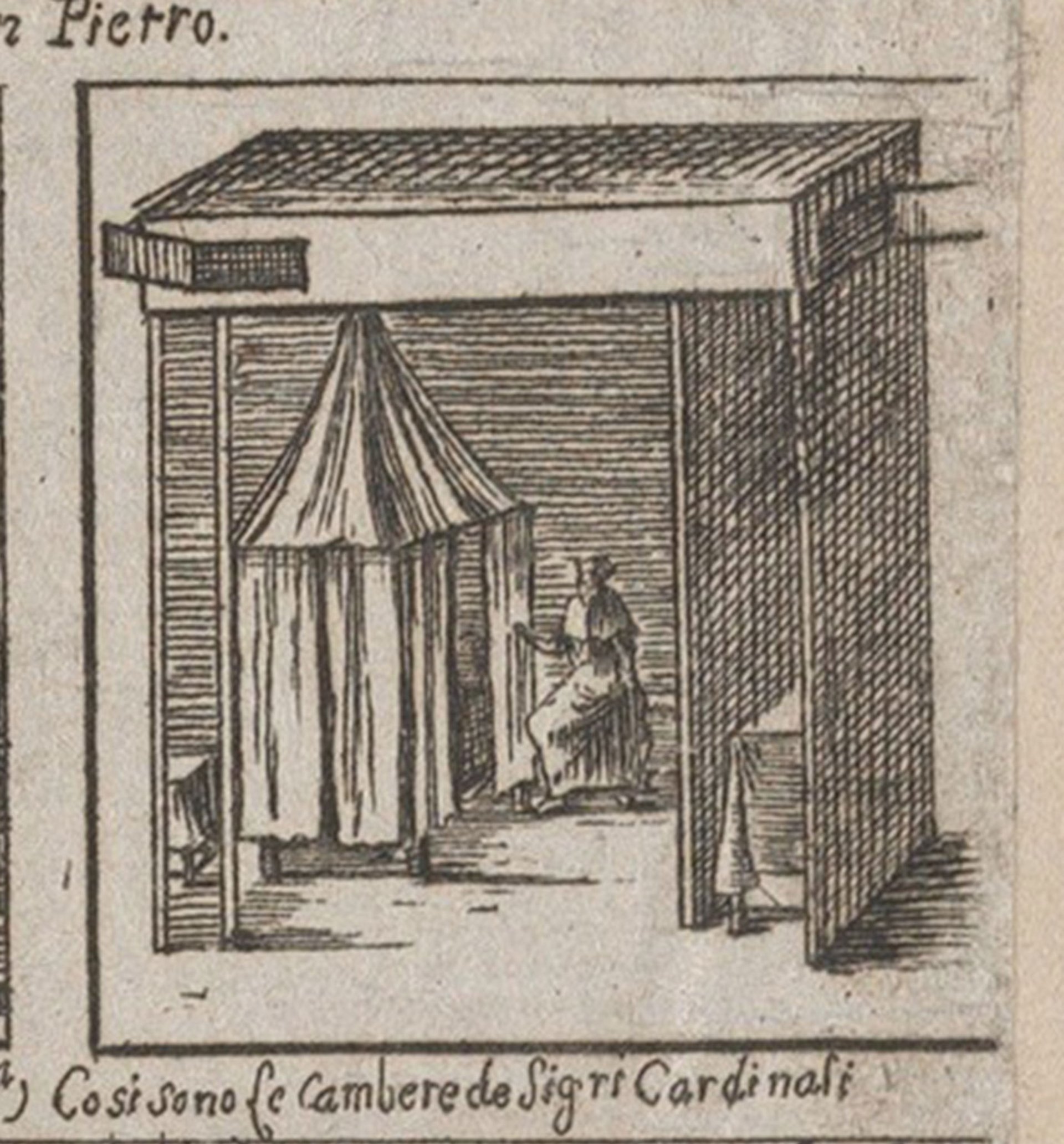

These conclave engravings are without exception centred on the floorplan of the apostolic palace in the Vatican, with numbered keys to the positions where each cardinal was based, in pop-up timber-framed, cloth-covered “cells” or cubicles, each cell with its own sitting and sleeping areas. These cells were set up in the Sistine Chapel in late 15th or early-16th century conclaves, when there were 20 or so cardinals present.

But, according to DS Chambers, writing in the 1978 Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, as the number of cardinals grew in the 1500s, these cubicles came to be spread out more spaciously around the apostolic palace. Yet there would usually be two or more to a room or gallery, presumably to ensure some manner of collective self-regulation, with conclave negotiations going on, sometimes in the palace privies, by day and night.

Detail from a 1667 papal conclave etching showing an artist’s impression of one of the cells—pop-up timber-framed, cloth-covered cubicles—that were assigned to each cardinal for the duration of the conclave The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Google Arts

Part of the fascination of these engravings is in discovering where great patrons of the arts (whether as cardinals or in future as popes) might find themselves. Cell positions were drawn by lot, and cardinals might bunk up in their silk-covered cells in any one of the palace’s marbled halls, including one of the four celebrated Raphael stanze rooms painted by Raphael and his assistants for Julius II in the 1510s. Some positions under particular wall paintings developed a reputation for being lucky.

According to L. D. Ettlinger, writing in The Sistine Chapel before Michelangelo (1965), the “belief seems to have been that the cardinal to become pope would obtain the cell beneath Perugino’s painting of Christ giving the keys to St. Peter…. But a sporting chance was also held for the cardinal in the furthest cell from the altar beneath the opposite wall, under the detail in Signorelli’s Last Acts of Moses, showing Moses handing on the golden rod to Joshua”.

The papal master of ceremonies Johann Burchard recorded in his memoirs that when Giuliano della Rovere was elected Julius II in 1503—after which he duly became Raphael’s papal patron while also commissioning Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and Donato Bramante to draw up the plans for a new St Peter’s Basilica—della Rovere’s cell had been positioned in one of these auspicious places, beneath Perugino’s wall painting Christ giving the keys to St Peter. Paul III, another great papal Maecenas, was elected pope after his conclave cell had occupied the same position in 1534.

The proceedings around the pope’s death and succession had real-world consequences as Rome’s great families and Europe’s monarchs sought to influence the papal election. This can now be seen as a millennium-long pre-echo of the diplomatic side meetings that took place at Pope Francis’s funeral on 26 April, with world leaders huddled in the nave of St Peter’s to discuss peace negotiations around Russia’s three-year-long invasion of Ukraine.

An etching published by De Rossi, in Rome, to mark the 1667 conclave that saw Giulio Rospigliosi elected as Pope Clement IX The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Google Arts

The art historical context for the 2025 conclave

This year’s conclave will take place in Vatican City, with no outside communication for the cardinal electors until they choose a candidate by a two-thirds supermajority (in the past this has sometimes been a simple, one-vote, majority). In 2025, “no communication” means that all the conclave spaces will be swept for spying bugs and WiFi signals in the Vatican will be blocked.

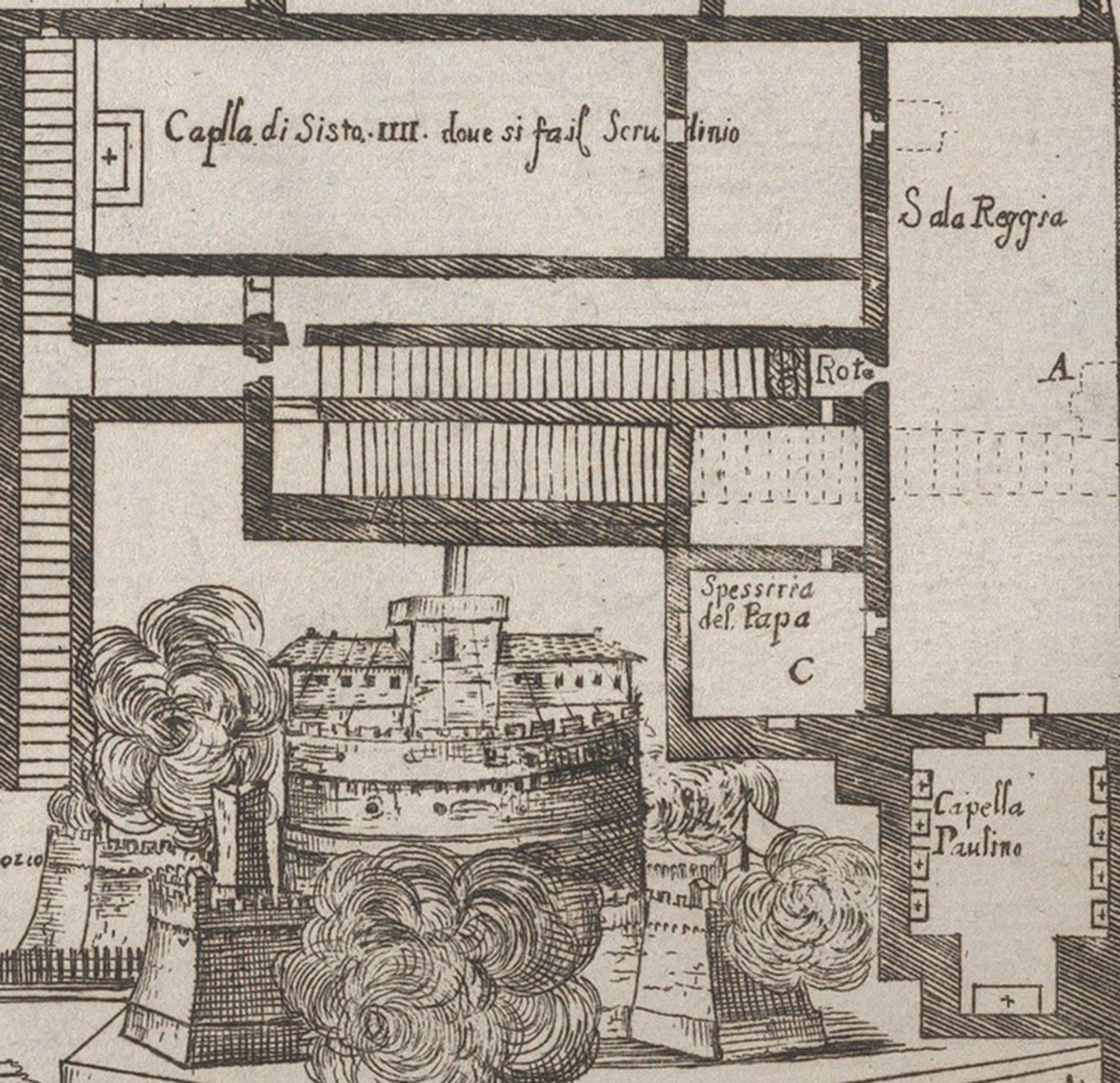

After leaving the Casa Santa Marta guest house, on the south side of the Vatican City, the 130 cardinals who are voting in 2025 will walk each day into the architectural and artistic tour de force that is the apostolic palace, built hard against St Peter’s. They will mount Bernini’s great double-flight Scala Regia (royal staircase), with its opulent baroque plays on perspective, to the lofty Sala Regia (royal chamber), where they will turn right to enter the Capella Paolina (the Pauline chapel built by Pope Paul III and adorned with Michelangelo frescoes of 1542-49) to gather and hear the first sermon of each voting day.

They will then process in pairs back through the Sala Regia (with Giorgio Vasari’s historical frescoes of papal political victories for company) and into the hallowed space of the Sistine Chapel with Michelangelo’s painted ceilings (1508-12) and his epochal Last Judgement (1536-41) looming over the earlier wall paintings by Perugino and Signorelli.

Cardinals in choral dress take their place in the Sistine Chapel in 2013, during the conclave that elected the late Pope Francis, with Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement looming over the high altar. Soon after the doors of the chapel would have been closed for a closed session of voting Abaca Press / Alamy Stock Photo

With the chapel doors sealed against the outside world the cardinals will vote twice a day until a candidate is selected, the decision signalled to the world by the burning of ballots to produce white smoke, emitted from a chimney in the chapel’s roof, and visible to the outside world. The prelude to a church official announcing “Habemus Papam”.

The idea of a closed conclave

A millennium ago, the idea of a college of cardinals to elect a new pope became the norm, while some 750 years ago it was established that the conclave of cardinals where a pope was selected—by acclamation or a majority ballot—be a closed session. The secret voting sessions were designed—if more in hope than expectation—to reduce the influence of the great warring medieval Roman families and patrons of the arts. This included the Colonna and the Orisini—not forgetting the Caetani, Barberini, Farnese, Sforza, Chigi, Pamphilj, Medici, Borgia and Borghese interests—or the financial and diplomatic inducements from the rulers of France, Spain, Austria or the Holy Roman Empire.

Closed conclaves were also intended to speed up proceedings, with both the Roman mob and Europe’s ruling powers impatient for a result. In the age of anointed monarchies—all the more so in the ages of Reformation and Counter-Reformation and the resulting religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries—the identity and political persuasions of a pope were of great political importance. In 2025, similar concerns agitate the supporters of the late Pope Francis who wish to see a successor who will stand up for his progressive legacy, his championing of the poor and of action to combat the global climate crisis, as well as his ability to speak truth to authoritarian power.

A detail from a 1605 conclave engraving showing food being brought to the Vatican apostolic palace, and checked before distribution. Beneath the image is the numbered list of the 66 cardinal electors piemags/rmn / Alamy Stock Photo

As for the Roman mob, it had grown in numbers periodically because, as Frederic J. Baumgartner points out in his book Behind locked doors: a history of the Papal elections (2003), until 1700 all prisoners in Rome were released at a pope’s death. This was “in imitation of Barabas’s release at the time of the crucifixion, and many returned immediately to the life of crime that had landed them in prison”.

There was also a tradition in Renaissance Rome, as Baumgartner records, that the house of a cardinal elected pope should become fair game for looting. This made the duration of a conclave the source of particular impatience to would-be looters.

An artist’s take on the papal conclave

The advent of printing engravings or etchings in quantity allowed for the commercial production of a series of artist’s takes on the papal elections. The earliest surviving printed plan for a papal conclave is from 1549-50, when Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte was elected Pope Julius III.

Engravings of conclaves from the 16th to 18th centuries survive, including in the collections of the Vatican Museums, the Metropolitan Museum in New York City and the British Museum in London. They constitute a visual source to add to what scholars mine in diplomatic correspondence or in recorded accounts of cardinals betting successfully on the result with Rome’s bookmakers in the 15th and 16th centuries before attempts were made to stamp down on that practice.

The Sistine Chapel

Since the building of the Sistine Chapel, for Pope Sixtus IV in 1473-81, most conclaves, starting with that to appoint Sixtus’s successor in 1484, have been centred around that fabled chapel, but with a notable century’s gap between the conclaves of 1774 and 1874. In 1779-80, Napoleon’s occupation of Rome forced the conclave to meet in Venice.

The next four conclaves, in 1823, 1829, 1830-31 and 1846, were based in the Capella Paolina of the pope’s summer palace, the Quirinale, built on Rome’s highest hill to avoid outbreaks of malaria down by the river Tiber. The advent of the first monarch of a united Italy, Vittorio Emmanuele—who took over Rome in 1871 as the national capital and the Quirinale as the royal palace—required the conclave of 1874 to move back to the apostolic palace in the Vatican.

A detail from a 1667 etching showing the heart of the papal conclave. with the Sistine Chapel (top left), the Scala Regia (middle left), the Sala Regia (top right) and the Cappella Paolina (bottom right). The caption to the Sistine Chapel indicates that the counting of votes took place there, a function sometimes assigned to the Cappella Paolina. The image of the Castel Sant’Angelo (bottom left) shows the cannon fire from the castle bastion to celebrate the appointment of a new pope Metropolitan Museum of Art and Google Arts

The Sistine Chapel was a regular home for the scrutineering of the cardinal’s ballots from the conclave of 1565-66 onwards. This scrutiny had previously taken place in the now lost Capella Parva of St Nicholas or in the Capella Paolina (whose structure was completed in 1538 for Paul III), while engravings from 1590 and 1605 suggest that the voting process still sometimes took place in the Capella Paolina, including when the Sistine Chapel was again pressed into service as a home for the cardinal’s temporary cells.

The election of Niccolo Sfondrato as Pope Gregory XIV, 1590

An etching of a plan of the conclave that opened in October 1590 following the death of Urban VII, is in the collection of the British Museum. In that election, Niccolo Sfondrato, Bishop of Cremona, a close friend of Philip Neri, the future saint, and one of seven cardinals deemed acceptable to King Philip II of Spain—who interfered in this conclave as never before—was elected Pope Gregory XIV. In his short reign he commissioned a lantern for St Peter’s to crown the completion of Michelangelo’s dome. After an election in which royal interference had been so blatant, and ambassadorial correspondence so full despite the cardinals taking vows of complete secrecy, Gregory in 1591 banned wagering on both papal elections and the length of papal reigns.

The 1590 etching indicates that, during the conclave that elected Sfondrato, eight cardinals had their cells in the antechapel of the Sistine Chapel—to the east of the dividing screen, or cancellata—but the remaining 58 attending were spread around the papal palace. Sfondrato’s cell was situated, with those of seven other cardinals, in the first half of what is now the Sala Ducale, which is entered from the Sala Regia through an entrance opposite the doors to the Sistine Chapel.

The neighbouring cells included those of Francesco Sforza, who had strongly opposed the bookies’ favourite Marcantonio Colonna before throwing his support behind Sfondrato at the crucial moment; Girolamo Mattei, brother of Caravaggio’s celebrated patron Chiriaco Mattei; and Alessandro di Ottaviano de’ Medici, archbishop of Florence, who, as Leo XI, became pope for under a month in 1605. The etching carries a note that the cardinal electors, in order to eat, walked down to the south end of Leo X’s loggia—whose decoration had been painted by Raphael and his assistants 70 years earlier—to take a flight of stairs to a lower floor of the palace.

The election of Camillo Borghese as Pope Paul V 1605

An etching showing the plan of the papal palace, illustrated with scenes from the conclave of May 1605 where Camillo Borghese was elected Pope Paul V, carries a high degree of detail in images and captions. The cell set up for Borghese—the celebrated supporter of Galileo Galilei who as pope commissioned Maderno to complete the facade of St Peter’s—was located in the Hall of Constantine, the last and largest of the four rooms in the former apartments of Pope Julius II that Raphael spent 12 years decorating before his untimely death in 1520. Borghese shared that space with six other cardinals, including his immediate neighbour Odoardo Farnese, a great great grandson of Pope Paul III and noted patron of Annibale Carracci.

One intriguing reference in the etching is to an upper window in the Cappella Paolina (then still visible from St Peter’s square before being obscured by Maderno’s facade to the basilica) which it is stated would be used to signal the name of the winning candidate to the waiting world.

The election of Giovanni Battista Pamphilj as Innocent X in 1644

Following the death in 1644 of Urban VIII—another great papal patron of the arts, whose recently restored memorial by Bernini in St Peter’s was the site of one of Pope Francis’s last visits before his death—he was succeeded by Giovanni Battista Pamphilj as Innocent X. Innocent was immortalised, with a famously forbidding expression, in Diego Velazquez’s matchless portrait in the Doria Pamphilj collection in Rome and by Francis Bacon’s screaming Pope riffs on that great painting.

An etching of the conclave that elected Pamphilj, in the collection of the British Museum, shows that scrutiny of the ballots in 1644 was conducted once more in the Sistine Chapel. Pamphilj’s cell, numbered 15, was one of 20 placed in the great Loggia della Bendizione, designed some 30 years before by Maderno for Paul V. The cell was sited immediately, and perhaps auspiciously, behind the central window of this gallery from which a new pope, elected in conclave, is presented to the waiting world.

How etchings were modified between conclaves

The conclaves of 1667, when Giulio Rospigliosi was elected Pope Clement IX, and 1669-70, when Emilio Bonaventura Altieri was elected Pope Clement X, demonstrate how one leading Roman publisher, Giovanni Giacomo de’ Rossi, whose company was additionally responsible for a dozen illustrated books of Roman fountains and palaces, would adapt an existing etching for a new conclave. In the 1669 etching, the depictions of the previous pope’s death, the proceedings of the conclave and the acclamation of a new pope remain unchanged from 1667, as do their captions. But the names of the late pope, the dates of his death, the numbered names of the cardinals and the location of their conclave cells, have all been modified on the metal etching plate for the 1669-70 conclave.

Detail from a 1667 conclave engraving showing the four stanze decorated by Raphael in the 1510s. The numbered key indicates that the second room to the left, the Stanza della Segnatura (home to Raphael’s masterwork The School of Athens), was occupied by the temporary timber-framed cells assigned to Angelo Cesi (No 42) and Giulio Rospigliosi (No 43), who was elected Clement IX during the 1667 conclave Metropolitan Museum of Art and Google Arts

Rossi’s etching for the 1667 conclave, in the collection of the Met, shows that Rospigliosi’s conclave cell was placed with that of Cardinal Angelo Celsi, a member of a notable Venetian family, in the Stanza della Segnatura, where Raphael painted his masterwork The School of Athens (1509-11). Rospigliosi had long since established himself as a patron of the arts.

Three decades earlier he had commissioned Nicolas Poussin to paint the celebrated A Dance to the Music of Time (1634-36), a painting that stayed in the Rospigliosi family until the early 19th century before being acquired in 1845 by the fourth Marquess of Hertford, from whom it was inherited by his son Richard Wallace, creator of the Wallace Collection, in London.

For the conclave of 1669-70, the updated plan, an example of which is held in the collection of the British Museum, shows that Emilio Bonaventura Altieri, the future Pope Clement X, occupied space in a room, on the “new” section of the apostolic palace overlooking St Peter’s Square. This is now the wing from which modern Popes deliver their Angelus blessing. He shared space with three others, including Giacomo Rospigliosi, nephew of Clement IX, and for a long time leader in the voting, who early in proceedings secured 33 votes, just seven shy of the 40 required.

The conclave today

The temporary, pop-up nature of the conclave’s furnishings in the Renaissance and early modern period is reflected in the Sistine Chapel’s preparation for conclaves in the 21st century. In the Sistine Chapel the Vatican joiners have been busy—as busy as they were in earlier centuries putting up temporary wood-framed cells—in installing a temporary wooden floor, overlaid with carpet. This both protects the mosaic floor of the chapel, makes the chapel warmer in winter, and muffles the acoustic, while also providing a place to conceal debugging and WiFi jamming equipment. Vatican staff are also installing a temporary stove and chimney, to be used to signify voting results to the outside world—black smoke for no result, white smoke to signal the election of a new supreme pontiff.

The most recent update to conclave regulations came in a letter issued by Benedict XVI in February 2013, six days before his resignation as pope, in which a “traditional norm” was reinstated “whereby a majority vote of two thirds of the Cardinal electors present is always necessary for the valid election of a Roman Pontiff”. It was also ordered that “no one approaches the Cardinal electors while they make their way from [their lodgings in] the Domus Sanctae Marthae to the apostolic Vatican palace”.

As much as at any time in the past millennium the need to conduct the conclave in a secure, closed, communication-free environment, without challenge or controversy, remains paramount.