Changing the narrative: National Public Housing Museum opens in Chicago – The Art Newspaper

The National Public Housing Museum (NPHM) on the West Side of Chicago, a museum that tells the history of public housing in America, will open on 4 April after nearly two decades in development. The 45,000 sq. ft, three-storey museum repurposes the last remaining building of one of Chicago’s oldest federal housing projects, the Jane Addams Homes, which were designed by the architect John Holabird, opened in 1938 and were home to thousands of families until they were vacated in 2002.

The vision for the museum came during the wake of the Plan for Transformation, an urban renewal plan that the city of Chicago launched in the late 1990s to reimagine the future of public housing and deal with racialised poverty and decaying buildings. At the time, the plan included the demolition of several high-rise public housing homes. Noticing that their homes were being erased, public housing residents came together to envision a memorial.

The narrative about public housing is about demonising the working class

“The residents wanted a museum that would call on the power of place and memory to challenge the mainstream narrative about the failure of public housing in the US,” says Lisa Yun Lee, the NPHM’s director and chief curator. “It’s now a history museum that meets a world-class art museum, which is what makes it unique.”

‘Site of conscience’

The project was spearheaded by the late Deverra Beverly, a public housing commissioner in Chicago. Working with residents, advocates, scholars and preservationists, Beverly established the museum as a “site of conscience”, a formal designation by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience for locations significant to the history of social justice, such as the Tenement Museum in New York. The $16.5m project was realised with funding from the city of Chicago, which contributed around $4.5m, the state of Illinois and private donors.

Marisa Morán Jahn (right) and Miss Elaine, a Chicago public housing resident, with HOOPcycle, a mobile interactive art installation

Courtesy National Public Housing Museum

“It’s both a capital project and an exhibition project that has engaged with a wide range of guest curators—many of whom are public housing residents—and scholars from various fields,” Lee says. “There’s also an extraordinary and diverse group of artists at the foundation of the museum.”

The museum has a small permanent collection and archive funded by the Mellon Foundation, and it has worked with public housing residents to collect objects that curators believe tell the best stories about public housing in the US. Its rotating permanent collection galleries feature labels written in collaboration with public housing residents and some loaned objects.

“We had to be really innovative in creating this museum because the archives were not filled with objects for us to use,” Lee says. “The stories and artefacts of people who are living in poverty and in the so-called marginal society are not preserved with the same voraciousness as objects by wealthy white men.”

She adds: “We are committed to collecting objects that make people understand that these stories are valuable to us as a nation, and that we can learn from the lives and the survival and thriving of public housing residents.”

In addition, the museum features several contemporary art commissions that tell stories of resilience, like the monumental permanent mural ReCreation by Marisa Morán Jahn, an artist and co-founder of Carehaus, a forthcoming co-housing project in Chicago and Baltimore for elderly residents and their families and caregivers. The work, an amalgamation of black-and-white photographs showing moments of joy, covers three floors of the museum and celebrates solidarity in public housing communities.

Community-minded works

Jahn completed the work while participating in the Artist as Instigator programme, a $10,000 unrestricted residency the museum launched in 2019 to promote community-minded works, sourcing the images from the archives of the University of Baltimore. The artist was given permission to remix the photographs, which showed “beautiful moments of organising and peacemaking”, and not the “civil riots that contemporary audiences in Baltimore were used to seeing”, she says.

“I once lived in public housing and, like many people, didn’t realise it was public housing; it was just where I could afford to live,” Jahn says. “But I remember thinking that it was the first time I lived somewhere multi-generational, where there was a sense of sharing and mutualism.”

She adds: “The narrative about public housing in the US is about demonising the working class or low-income people. I wanted to bring a new lens of dignity to the issue through my experience and the many people that I have worked with.”

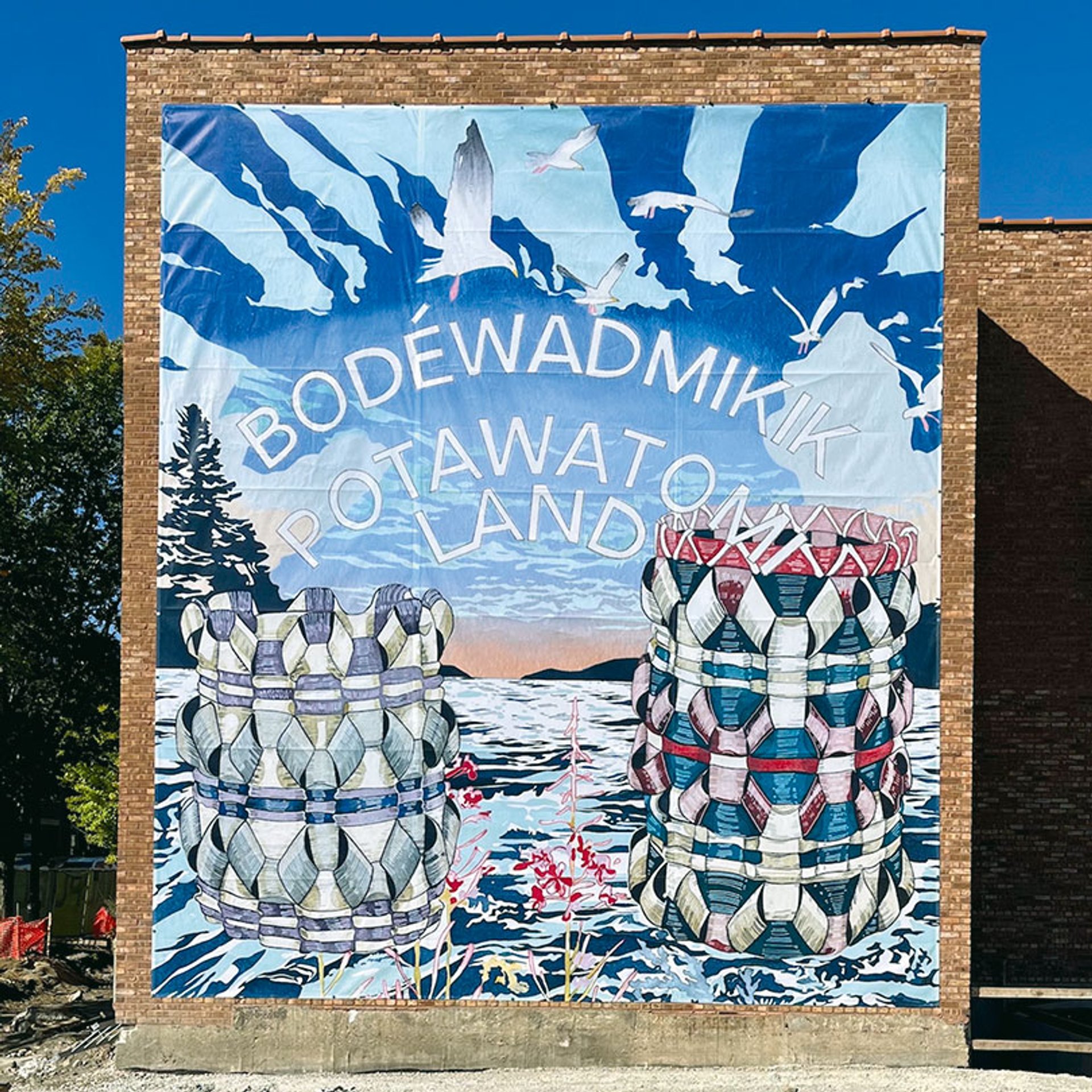

There are also several temporary exhibitions like Still Here (until 20 April) curated by Lucy Mensah, the assistant professor of museum and exhibition studies at the University of Illinois Chicago, which featured more than ten artists and activists exploring histories of displacement and forced removal, specifically as it relates to Indigenous communities.

One highlight of the exhibition was the 40ft-tall work Still Here: Zhegagoynak, by the Ojibwe artist Andrea Carlson, suspended on an exterior wall of the building and linking the history of displacement of Indigenous communities with the redlining (withholding of financial services) of African American communities. It features lettering in Potawatomi and English, taking words from treaties that caused displacements, such as the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, the 1816 Treaty of St Louis and the 1795 Treaty of Greenville.

Andrea Carlson’s Still Here: Zhegagoynak (2024) explores displacement and redlining of Indigenous and African American communities respectively

Courtesy National Public Housing Museum

Beyond its art offerings, the museum has launched several civic programmes that aim to uplift the community like the Cultural Workforce Development Program, which offers training and professional growth opportunities, and “acknowledges the lack of diversity and lack of inclusivity that often exists at contemporary museums and art spaces”, Lee says. The museum has hired around ten public housing residents who have participated in the programme as educators and visitor service staff.

Lee hopes more members of public housing communities will become involved with the museum in the years to come to expand the public perception and understanding of public housing and other social justice issues. “In order to preserve history, you have to make it relevant to contemporary social justice issues,” she says. “In order to solve the problems of today we have to go back in time and ask what we have yet not learned.”

- National Public Housing Museum, Chicago, opens on 4 April